My Academic Journey

Nine universities, four continents, inglorious persistence, and luck.

This page is part of my advice pages.

Read This First

I wrote this page as a brief chronicle of my experiences in academia as a student and a career seeker. I've shared parts of this story with junior researchers, students in my classes, and colleagues, and they often want to know more. I especially wanted to share certain aspects: my long path to career stability, uncertainties I faced, obstacles to success and well-being, and the pervasive role of luck.

The narrative below includes being a student, employee, or visiting researcher at nine universities (University of Mary Washington, Virginia Tech, University of Maryland, Macquarie University, National University of Singapore, Carnegie Mellon University, University of Edinburgh, University of Cincinnati, Penn State University) across four continents (North America, Australia, Asia, Europe). It also shows how many times I've changed or added research areas: I worked in graph theory and bioinformatics as an undergraduate; commonsense reasoning, dialog systems, and natural language processing (NLP) as a graduate student; NLP and privacy as a postdoc; and NLP, privacy, and computational social science as a faculty member. Accumulating this many moves and research changes wasn't intentional, but it produced stories that I'm glad to share if they're helpful.

The chronicle also begins early. Parts of my K-12 education led into my career path and my research interests.

Thoughts on Failure, Thoughts on Competition, Thoughts on Uncertainty, and Where I'm From expand on some experiences I describe on this page.

Privilege and Vulnerability

I belong to privileged demographics for gender, sexual orientation, and race (sort of—race is complicated). Some childhood experiences gave me advantages toward an academic career. Additionally, having a tenure-line faculty position is a privilege. The academic job market is an immense barrier of competition and luck, and it prevents many equally deserving but less fortunate people from becoming faculty.

I can share more about my academic journey than many other people, some of whom are experiencing equal or greater challenges. I have sufficient distance from the negative experiences I describe that sharing them costs me little in peace of mind. For example, I no longer have to worry about people thinking that I'm a disaffected middle schooler, a tragically idealistic college student, or a perpetual postdoc who won't find a career position. Instead, privilege allows me to redeem my unpleasant experiences by sharing them with people who might be able to learn from them.

Chronicle

- K-12

- Interests

- Obstacles

- What I Wanted to Be When I Grew Up

- Extracurricular Activities

- Early Encounters with Higher Education

- College

- Majors and Classes

- Hillcrest

- Career Thoughts

- Early Research Experiences

- Applying to Graduate School

- Graduate School

- The First Year

- Challenges

- Research Focus

- Australia and Singapore

- Graduation and Unemployment

- Postdoc Positions

- Affiliations

- Contrast

- Research

- Scotland

- Academic Job Search, Part I

- Tenure-Line Faculty Position #1

- Faculty, Finally

- Academic Job Search, Part II

- Tenure-Line Faculty Position #2

- The Present

- What I Enjoy

- What Surprises People

- It's Still a Job

- 2024 Update: Tenure

- Acknowledgements

"Shomir Wilson is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the University of Cincinnati, where he leads the Human Language Technologies Lab and is a member of the Institute for Analytics Innovation. His interests span pure and applied research in privacy, natural language processing, and data science. Previously he was a postdoctoral fellow and a lecturer in Carnegie Mellon University's School of Computer Science, and he has held NSF-sponsored visiting affiliations at the University of Edinburgh, the National University of Singapore, and Macquarie University. He received his Ph.D. in Computer Science from the University of Maryland in 2011."

— Job talk bio for my interview at Penn State, in February 2018.

"You're almost a professor, right?"

— A friend, during a conversation with me in late 2013.

K-12

Interests

I grew up in suburban Virginia. I don't remember having a favorite subject in elementary school, but one highlight was a summer governor's school program where I learned to program in BASIC. It was my first programming language, and afterward I continued programming as a hobby on a home computer. Over the next several years I would use books to teach myself C, C++, Java, and HTML.

In late middle school and through high school, math and English became my favorite courses. Algebra seemed to press beyond the fabric of reality, and later, so did calculus and statistics. In English classes I enjoyed learning about grammar and style, and writing well gave me satisfaction.

In high school I took programming courses in Pascal and C++, though I had already learned the latter on my own. I was achievement-oriented in my classes, aiming for the highest grades I could get.

Obstacles

I was a frequent target of bullying in middle school and early high school, for a variety of reasons. My ethnicity was indeterminate from my appearance, and I was the target of a variety of racial slurs and taunts. Persistent rumors circulated about my sexuality, though I've always been open about who I am (i.e., a straight cisgender male); those rumors led to physical violence and the worst of the verbal abuse. I was also shy, unathletic, and poorly dressed. Teachers often witnessed the bullying but rarely intervened. I had few friends, and for a few years the bullying eclipsed my enjoyment of school. I share more about bullying in Where I'm From.

During middle school I also suffered from obsessive-compulsive disorder, although I did not seek a formal diagnosis. I was often uncomfortably preoccupied with counting things, collecting things, knowing the time, and abstract meta-thoughts. These problems interfered with my ability to sleep and to enjoy everyday activities. I didn't seek help for it, as I didn't know it was a condition with a name and possible treatments. The condition diminished and then disappeared in early high school without intervention.

What I Wanted to Be When I Grew Up

My first career goal that I can remember was to be an astronomer. The great unknowns beyond the Earth were (and still are) interesting to me. I wasn't interested in stargazing, telescopes, or the constellations, but I read many books about the planets of our solar system, phenomena further away, and space exploration.

In seventh grade I took a test to assess my aptitude for a variety of career paths. "Air traffic controller" was my best match. Meanwhile, playing strategy games on my home computer shifted my career thoughts: I decided that I wanted to be a video game developer. Separately, movies and books about spies and espionage also made me think about working in the intelligence community.

Extracurricular Activities

I played the violin for many years in elementary school and middle school. Sometimes I enjoyed it, but I was perpetually anxious about performing for an audience. In retrospect it wasn't a good fit for me, and other instruments might have been better.

I was on the debate team for all four years in high school and the quiz bowl team ("Battle of the Brains", locally) for two years. I competed in the Lincoln-Douglas style of debate, and it had an immense impact on my verbal skills, socialization (e.g., the friendships I gained), self confidence, leadership skills, and how I thought about the world around me. My enjoyment of debate as an activity diminished in college, but many of my best high school memories involved debate tournaments or spending time with debate friends.

Early Encounters with Higher Education

Both of my parents were faculty at regional colleges when I was little, and during the summer they sometimes left me in their offices or in the library while they taught. I enjoyed making paper airplanes and throwing them from balconies in atriums. I browsed the library stacks and memorized where in the Library of Congress Classification I could find books that I enjoyed (PZ and later PS). Outside, I explored the quads and the landscape. I was oblivious to the people and activities around me, but at an early age I became comfortable with being on a college campus.

Between my junior and senior years of high school, I took a class in discrete math at the University of Mary Washington. I was surprised at how a college course wasn't fundamentally different from a high school course: it still consisted of lectures, homework, and tests. The course was challenging at times, but not impenetrably so.

For college, I applied to Virginia Tech, the University of Virginia, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Virginia Tech and the University of Virginia admitted me, and I didn't know how to decide between them. I was oblivious to factors like graduation rate, relative prestige, majors offered, what the dorms were like, or campus amenities. I think I chose Virginia Tech because its name suggested to me that it was a better school for computer science, which seemed like a good major to start with.

College

Majors and Classes

I entered Virginia Tech majoring in computer science and minoring in mathematics and philosophy. By the time I graduated I upgraded both minors to majors, and I accumulated enough credits to earn three separate bachelor's degrees. I typically took 18 credits in a semester, though a few times I took 15 or 20.

Some of the classes I particularly enjoyed:

- Programming Languages (i.e., a course comparing programming language paradigms, rather than a course about how to write code) was my first exposure to programming paradigms outside of procedural and object-oriented. Functional and logical programming languages were very different from anything I had seen before.

- Intro to Computer Engineering showed me the stack of technologies from hardware gates up to assembly language, removing the mystery of how computers compute.

- Compiler Design and Construction showed me the stack of concepts from assembly language up to high-level programming languages. It also introduced me to grammar formalisms, which contributed to my future interest in NLP.

- A special topics course on Wittgenstein, a philosopher of language, also contributed to my future interest in NLP.

- Modern Logic introduced me to critical thinking as an explicit concept, and it continues to have an impact on how I make or evaluate claims.

- Combinatorics and Graph Theory was inexplicably fun and probably the easiest-for-me upper-level math course I took.

- Men's Issues encouraged me to reflect on my identity and growth. It was also my introduction to feminism.

Mathematics was the major I had the most difficulty with; I spent more time on math homework and worried about my grades in math classes more than any others. Number theory was inexplicably hard for me, and it was the only class I've ever had to drop and retake. Computer science was neither especially easy nor difficult, but it felt like a more natural fit. Meanwhile, philosophy satisfied a need I had discovered in high school debate for abstractions and exploration of ideas.

I was quiet in classes. I didn't have much to say because I was often uncertain whether I truly understood the material, and I doubted that I was following it as well as my classmates.

Hillcrest

Through most of college I lived in the Hillcrest Community, a themed housing program run by University Honors. About a hundred students participated in the community by living in Hillcrest Hall, with majors from across the university. We read books and articles together and discussed them in a special class that we typically ran ourselves. Periodically we had semi-formal dinners with invited speakers who led conversations on a variety of topics. The dorm also contained offices for Honors faculty and staff, whom I interacted with often. Dr. Jack Dudley, the director of the program, was particularly generous with his time when speaking with undergraduates. He remains an inspiration in my career.

I continue to reflect on what Hillcrest was intended to do. The general goal was to create thoughtful scholars who aimed for excellence in their studies and impactful careers beyond. One specific goal was to train students to apply for and win major national fellowships, like Goldwater, NSF GRFP, Fulbright, Marshall, and Rhodes. Many of my peers navigated around those pressures or found them easy to deal with, but Hillcrest's idealism mixed with the ambitions that I already had, and the expectations that I had for myself during college were sometimes unrealistic. Not meeting those expectations led to fatigue and periods of disillusionment. I discuss this more in Thoughts on Competition.

In spite of the pressures, Hillcrest's welcoming, supportive environment was important to my success in college. Socially, I associated with Hillcrest more than any of my majors or student organizations. It was the source of most of my college friends, some of whom I remain close to.

Career Thoughts

Early in college, I thought about becoming either a software engineer in industry or working for the federal government in the intelligence community. Software development gradually became less interesting to me, though it remained a practical, reasonable option. I did a summer internship at a large tech company and didn't feel the level of enthusiasm that I wanted as part of a career.

About halfway through college I began thinking seriously about a career in academia. Liberal arts faculty inspired me to want to lead classroom discussions, and faculty in my technical courses inspired me to want to guide students through complex material with infectious enthusiasm. My favorite professors seemed to love their jobs. I knew I would have to go to graduate school and get a PhD, but that seemed more like a path than an obstacle.

Early Research Experiences

I worked on two undergraduate research projects. The first was in computational mathematics, and the second was in bioinformatics. Both involved graph theory, a topic I had enjoyed learning about in courses, but neither of these projects were as interesting to me as I had hoped they would be. Neither resulted in publications, and in retrospect there were predictable reasons why they weren't more successful.

Meanwhile I performed two independent studies with faculty in philosophy, exploring ideas in greater depth than we could in a traditional course. I published the term paper from one of my independent studies in an undergraduate journal, and I presented a term paper from another course at an undergraduate philosophy conference. I was enthusiastic about philosophy, but I didn't think I could keep up with the jargon and the sheer volume of reading well enough to make it a career.

I was aware of artificial intelligence as a research area, and it sounded interesting. However, I didn't have the option to take a class in it and it seemed vaguely out of reach. I didn't yet know what natural language processing was.

Applying to Graduate School

I submitted graduate school applications during my fourth year of college, stating in my application materials an interest in programming languages research. However, it took me a second year of applications to get the results I wanted. I explain in Thoughts on Failure that my first round of applications was unsuccessful, and I stayed in college a fifth year to improve my portfolio and try again. The failure of the first round was devastating to my confidence, and I felt strange going through the activities of a final year again. When I graduated, any happiness that I felt competed with emotional exhaustion.

During the summer between college and graduate school, I worked a series of jobs for a temp agency. I was very briefly an assistant window installer and a store fixtures assembler.

Graduate School

The First Year

Prior to starting graduate school at the University of Maryland, during an open house for admitted applicants, I was scheduled to meet three professors whom I had expressed interest in working with on research. My first meeting was double-booked with another admitted student; the professor talked with me for half a minute and then spoke exclusively with the other admitted student for the rest of our half-hour session. (Awkwardly I sat in silence, nodding along.) The second professor did not participate in the visit day, leaving an empty slot in my schedule. The third professor talked with me one-on-one for our full scheduled time. Later, he would become my advisor.

I entered the PhD program as a teaching assistant. I was a grader in my first semester and then led a discussion section in my second semester. At first I dreaded every discussion session and every student who approached during office hours, but then I became used to these modes of interaction and began to enjoy them. Helping students understand material, both individually and as a classroom audience, was satisfying in the way that I hoped it would be. Sometimes I noticed that I echoed strategies and mannerisms from my favorite faculty in college.

Toward the end of spring semester I once again approached the faculty member whom I had spoken with at length on visit day. He admitted me to his lab, and I held research assistantships for the remainder of my graduate studies.

Challenges

I struggled with the sudden lack of a built-in social environment like Hillcrest. My graduate school experience was more solitary than I would have wanted, for specific reasons beyond the scope of this chronicle. I also would have wanted more ways to make friends among my graduate student peers without the relentless pressure to discuss research. At times, the lack of social support made it challenging to concentrate on my work.

Graduate school classes were very difficult for me, but it was a continuation of a trend I noticed late in college: I was gradually becoming less able to concentrate on studying, perhaps partly from age and partly from burnout on school. (I had briefly considered a year or two in industry before the PhD, but I worried that I wouldn't have the self-discipline to return to school after a break.) I earned some surprisingly low grades on term projects and tests. In one course during my first semester, the professor gave me a soft offer for a research assistantship halfway through the semester—to begin the following semester—but I performed so poorly in the remainder of the course that he rescinded it.

Research Focus

I had professed an interest in programming languages research in my graduate school application, but by the time I arrived at Maryland I knew I wanted to do research in artificial intelligence instead. It seemed daunting, but the philosophical connections interested me, and I hadn't yet found research that I was enthusiastic about.

My advisor's lab focused on commonsense reasoning and conversational systems. I worked on these topics for about two years and then, with my advisor's permission, began working in a different direction. Conversational systems and commonsense reasoning seemed to be at a low point in their popularity: memories of the "AI winter" persisted among senior researchers, and practical examples like Siri and Alexa hadn't yet arrived. Instead I became interested in making data-driven claims about language use. I took a two-semester natural language processing (NLP) course series that gave form to my interest in working with language data.

Australia and Singapore

I had wanted to study abroad in college, but I never had the time or energy to make it happen. During my fourth year in graduate school I applied for an NSF fellowship to be a visiting researcher at Macquarie University in Australia during their winter (summer in the USA). Originally I didn't plan to apply: my first reaction after reading the email announcing the call for applications was to delete it, thinking my odds were too low. A few weeks later I found the email again and grudgingly applied, still thinking it was a waste of time. Months later, I was astounded to receive it.

Receiving that fellowship—and a similar one the next year to be a visiting researcher at the National University of Singapore—were pivotal to my morale in graduate school, my future travels, and the trajectory of my career. The research I performed abroad was only a modest gain for my portfolio, but the travel gave me something to look forward to, a welcome break from my typical activities in graduate school, and an accomplishment to think about when I felt low. I had long wanted to experience living and working abroad. At times I was still learning how not to be an "ugly American", and in retrospect I'm grateful that my hosts were patient.

Graduation and Unemployment

Close to the end of my final semester in graduate school, a faculty member whose opinion I greatly valued (but not my advisor) became intensely critical and scolding of my work, both toward me and toward the professors I worked with. At one point they yelled their disapproval of me at my collaborators; though I wasn't present, I heard the commotion from down the hall. When I graduated I felt numb and uncertain whether I had done anything of value. In retrospect, I had: several publications went into or emerged from my dissertation, and it also led to several grant proposals. At the time, one thing that helped me feel less bad was the fact that I had a strong prospect for a postdoc position, as a collaborator in a government lab had all but promised me an offer.

Soon after I graduated, my collaborator explained an internal problem with funding; no offer would come. I was unemployed for a few months, searching for jobs. I applied for a variety of positions inside and outside academia, all the while uncertain of the value of my PhD and wondering if it was time to give up on becoming a professor. I received a few suspicious offers mid-summer, and it was painful to turn them down. I also received many rejections.

Toward the end of the summer, a friend sent me an ad for a postdoc position at Carnegie Mellon University. I had read about the opening before and previously decided not to apply to it, as it seemed out of my league and the focus seemed too different from my PhD research. However, receiving the ad from someone else made me feel obligated to perform due diligence. Grudgingly I applied, expecting it was a waste of time.

I was interviewed, taken seriously, and given an offer. I accepted it.

Postdoc Positions

Affiliations

During five years as a postdoc I held two, three, or four positions, depending on how you count them. Here is the maximal interpretation:

- Postdoc 1: I spent the first two years at Carnegie Mellon University in the Institute for Software Research, supported by my supervisor's funding.

- Postdoc 2: Next, I spent a year at the University of Edinburgh's Institute for Language, Cognition, and Computation, funded by an NSF postdoctoral fellowship that I applied for and received.

- Postdoc 3: Next, I spent a year back at CMU in the Language Technologies Institute. I was funded partly by an NSF postdoctoral fellowship (a continuation of Postdoc 2 above) and partly by co-teaching a course.

- Postdoc 4: Finally, I spent a year in CMU's Institute for Software Research, working again with my supervisor in Postdoc 1 and supported by his funding.

Five years was an unusually long duration for a computer scientist to be a postdoc. Most postdocs leave sooner for a non-fixed term job, whether in academia or industry. I knew what I wanted—i.e., a job offer to become an assistant professor—and it took me a long time to get it.

Contrast

Overall I was more productive and happier as a postdoc than I had been as a graduate student, though my frustration with the academic job market accumulated toward the end. Living in Pittsburgh was advantageous for personal reasons, and I had better social support than I did in graduate school. I was startled by my change in fortune: graduate school had ended in a crater, in the sense that the ending was almost maximally unpleasant while still producing a PhD. By joining CMU, I had gone from being an exhausted, demoralized, unemployed PhD graduate to working at one of the best-known places in the world for research in my discipline.

Research

I suddenly became a postdoc in usable privacy. At first I was worried that I might not enjoy it, especially remembering my graph theory and bioinformatics research during college. Rather than working in an area that I was already enthusiastic about (like NLP), I was trying something new and hoping I would enjoy it.

The transition was smoother than I expected. Many of the research methods I had picked up in graduate school remained relevant, and in retrospect that relevance is unsurprising: the PhD program prepared me to be a researcher in computer science. Over time, my skills with NLP became more relevant too, as I began developing projects in the overlap between my research areas. Obligations to help mentor PhD students and to work with collaborators meant that I often had several projects going at once. My work in graduate school had felt largely solitary, but my first postdoc position put me into a network of obligations and frequent interactions. It was the kind of change that I had wanted.

Research management became a larger part of my work. I began guiding students to perform the hands-on aspects of research, while I provided direction, feedback, and goals. I summarized findings for collaborators and discussed strategy with them. I also helped craft grant proposals. These were skills that I would need as a faculty member, and I was glad to discover that I enjoyed them.

Scotland

My first, second, and fifth years as a postdoc fit the above description, but in between, my two years on my NSF fellowship—one at the University of Edinburgh and one in CMU's Language Technologies Institute—were more like graduate school. I worked alone on a project, with feedback chiefly from one or two faculty members. The results from the project were modest. If instead I had stayed in my first postdoc position, my research output likely would have been greater, and I could have landed in faculty position more quickly.

I took the fellowship because it was an opportunity to fulfill a long-standing personal goal: to spend an extended period of time abroad, longer than my ten-week stays in Australia and Singapore. I wanted to know what it was like to live for a longer duration in a different country, and I wanted to explore Europe. The personal fulfillment was offset by the suspicion that I had lengthened my job search.

However, there were benefits. I greatly expanded my professional and personal networks in the NLP research community. It was easier for me to build these networks as a postdoc than it had been as a graduate student. Feeling like I belonged at conferences and could credibly call myself a researcher in this field was an improvement for my career, even if those gains were difficult to quantify.

Academic Job Search, Part I

The CS/IS faculty job market observes an annual cycle, with applications due in the fall and interviews during the subsequent spring. Typically people submit applications for just one or two years before they either receive an offer or pursue a non-academic career path. In contrast, I was on the academic job market for four years before I received my first offers. Toward the end, the duration, repetition, and feelings of futility wore at me like nothing I had done before. I kept going because I knew that I wanted to be a professor and because the only thing I could realistically imagine doing was trying until I got what I wanted.

My first year on the faculty job market was my second year as a postdoc, and I submitted relatively few applications that year, knowing it would be a tradeoff between accepting an offer and going to Scotland on the NSF fellowship. I received no screening interviews or on-campus interviews that cycle, so I sent out more applications next year and more the year after that. I received a handful of screening interviews but still no invitations to interview on campus. When my NSF fellowship ended I returned to the lab that I began with as a postdoc so that I could submit a fourth round of applications. This batch was larger than the previous three combined, and I experienced significant frustration and self-questioning about the meaning of what I was doing.

However, I received my first on campus interview invitations and my first offers. I accepted one of them, to join the University of Cincinnati.

Thoughts on Failure contains more about my academic job search.

Tenure-Line Faculty Position #1

Faculty, Finally

I arrived at the University of Cincinnati relieved to have a tenure-line faculty position but also wondering whether I would enjoy being faculty as much as I had predicted. Six years of graduate school and five years as a postdoc suddenly felt like a wager: I worried that the job I had prepared for would somehow fundamentally differ from my expectations. However, that uncertainty was an underestimation of my prior experiences. I had already gained research management skills, worked on grant proposals, and taught a class. I had room to improve these skills (and I always will), but I arrived with more preparation than many of my peers.

I began recruiting research advisees as soon as I arrived, and I created a lab. I submitted grant proposals for the first time as a faculty PI. I created and taught an NLP course sequence, relearning and learning anew some of the material.

Academic Job Search, Part II

There were several reasons why I felt a strong need to return to the academic job market, but they're beyond the scope of this guide. I needed to move, but given how difficult it had been to receive any offers, I wondered if I would be able to.

My fifth year on the academic job market appeared to confirm my suspicions: I had some remote screening interviews and some on-campus interviews but no offers. Fresh PhD candidates sometimes received positions that I applied for. I was as many years past completing my PhD as it took to earn my PhD, but the additional experiences since then didn't seem to be helping my cause. My frustration was immense, but it helped to talk with my growing circle of friends in academia. Travel also provided some relief.

I returned to the academic job market a sixth year, submitting more applications than the fifth year but not as many as the fourth. When I first read the ad for a tenure-line faculty opening in IST at Penn State, I decided not to apply. I was uncertain whether my research would fit the areas listed in the ad. However, IST appeared to have several tenure-line faculty openings that seemed appropriate for me, which was a good sign. Eventually I applied to all of them.

Penn State was one of several universities that invited me to interview on their campuses, and they made one of the three offers I received. I considered all three carefully and chose Penn State. After the pressures and uncertainty of my prior moves, I was glad to make one on my own terms.

Tenure-Line Faculty Position #2

The Present

As I write the first draft of this narrative (November 2021), I'm an Assistant Professor in the College of IST at Penn State. I supervise a lab of graduate and undergraduate researchers, and I support many of them on grants I receive. We work on problems in natural language processing, privacy, and computational social science. I teach courses for students at all levels, ranging from introductory courses for first-year college students to research-oriented courses for PhD students. I participate in service activities for my college, the university, and my research community. In my spare time I also work on my advice pages as a resource for students and faculty and as an outreach project. Being a professor entails a heavy workload, and I don't enjoy all the obligations equally. However, it also comes with flexibility, which I use to spend time on the kinds of work that I enjoy.

My career depends on scholarly activities where hard work is only a baseline, like publishing and winning grants. I retain a great need for luck. The possibility also exists that all those job application rejections were a sign that I should be doing something else. Time will reveal whether that's an understatement, but I can illustrate for the reader that it's possible to have the setbacks I've described and still have some success.

What I Enjoy

Some aspects of being a professor that I enjoy:

- Working with students: My interactions with them are often the highlights of my week.

- Working for the public good: The underlying goal of all of my work is to help people.

- Openness: I can talk with my family, friends, and the general public about most aspects of my job.

- Flexibility: Aside from meetings and classes, I can choose when and where I work (with the important caveat that I typically have a lot to do). I decide what research topics I work on, how to manage my lab, where to apply for funding, and whom to collaborate with. The teaching strategies that I use in my courses are mostly up to me.

- Intellectual stimulation: Research and teaching provide interesting problems to think about. Working at a university also lets me seek out interesting conversations with faculty and students on a wide variety of topics.

- Friendships: I have faculty friends across the country and in other parts of the world. I keep in contact with them and we sometimes meet at conferences.

- Working on a university campus: It tends to be a lively, engaging environment.

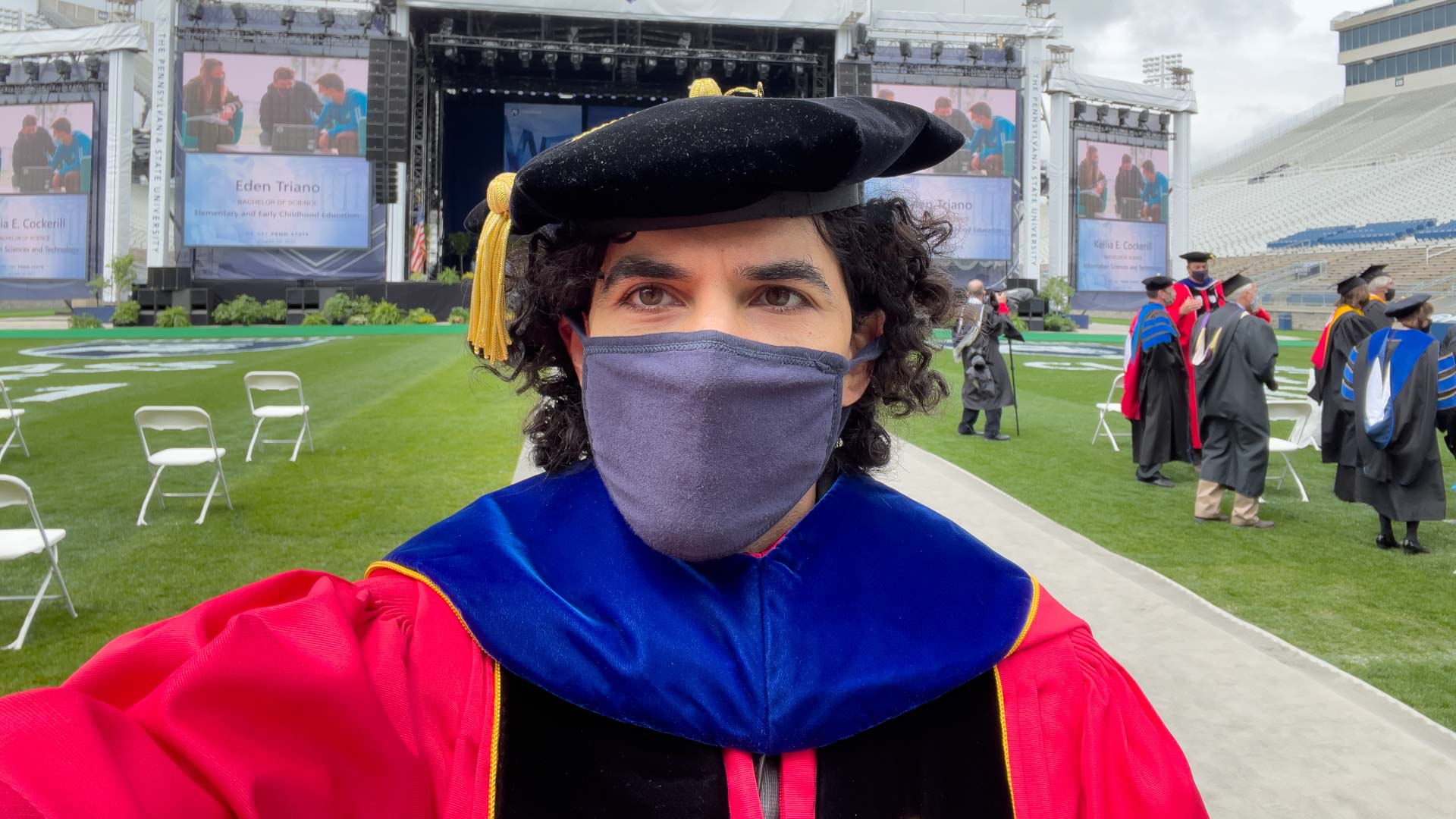

- Traditions: I always volunteer to participate in spring graduation. (I think graduations are more fun as faculty than they were as a student.) The annual cadence of spring semester, summer break, and fall semester is something I've become accustomed to and look forward to.

- Travel: Conferences in my field are important publication venues, and most change locations every year. I've traveled across the country and internationally to attend them, and I often allocate time to get to know the destinations outside of the conferences.

- Higher education's landscape: There are thousands of colleges or universities in the US, all with their own traditions, specialties, and personalities. Internationally, the organizations and cultures of higher education contrast in interesting ways.

What Surprises People

Some things that people don't expect about being a professor:

- How difficult it is to generalize what professors' jobs are like: Expectations vary enormously by university and by discipline. Some professors teach four or more courses per semester, while others may teach just one or two, and a few teach zero. Some devote at least as much time to research as to teaching, and some perform no research. Among those that have strong research obligations, some manage advisees who perform most of the hands-on tasks, some perform those tasks side-by-side with their advisees, some don't collaborate with their advisees, and some don't have advisees. There are also variations in publishing expectations (e.g., books, conference papers, journal articles), administrative responsibilities, and salary.

- The variety of obligations: When I tell people I'm a professor, a common question is "What do you teach?" At a research university, tenure-line faculty typically spend at least as much effort on research as they do on teaching. Additionally, service activities (which represent a third set of job duties) mean that teaching is actually less than half of a professor's expected effort. A more appropriate question might be "What's your discipline?"

- The work distribution for research: I'm more of a manager than a technical worker. I run the lab, while the students run the projects. For me, "research" is about providing the guidance; for my students, it's about the hands-on activities. This arrangement varies by discipline and by lab, but in computing it's common.

- How much time I spend on research finance: I frequently apply for grants from sources external and internal to the university. Grant money pays for PhD students' stipends and tuition, hourly wage positions for MS students and undergraduate researchers, study expenses, research equipment, travel to conferences, my summer salary, and other expenses. My Guide to Professorspeak reflects the importance of research finance.

- The lack of training: Faculty don't receive training to teach or to manage research teams. I was fortunate to have gradual introductions to both before I became a professor, but many start from scratch on those skills.

It's Still a Job

I've left some items out of this narrative that are too unpleasant, sensitive, or recent to properly share. Being a professor remains a job, and enjoying every obligation all the time is unrealistic. The pure "ivory tower" image of academia does not include the workload, the pressures, or the internal politics that make it real.

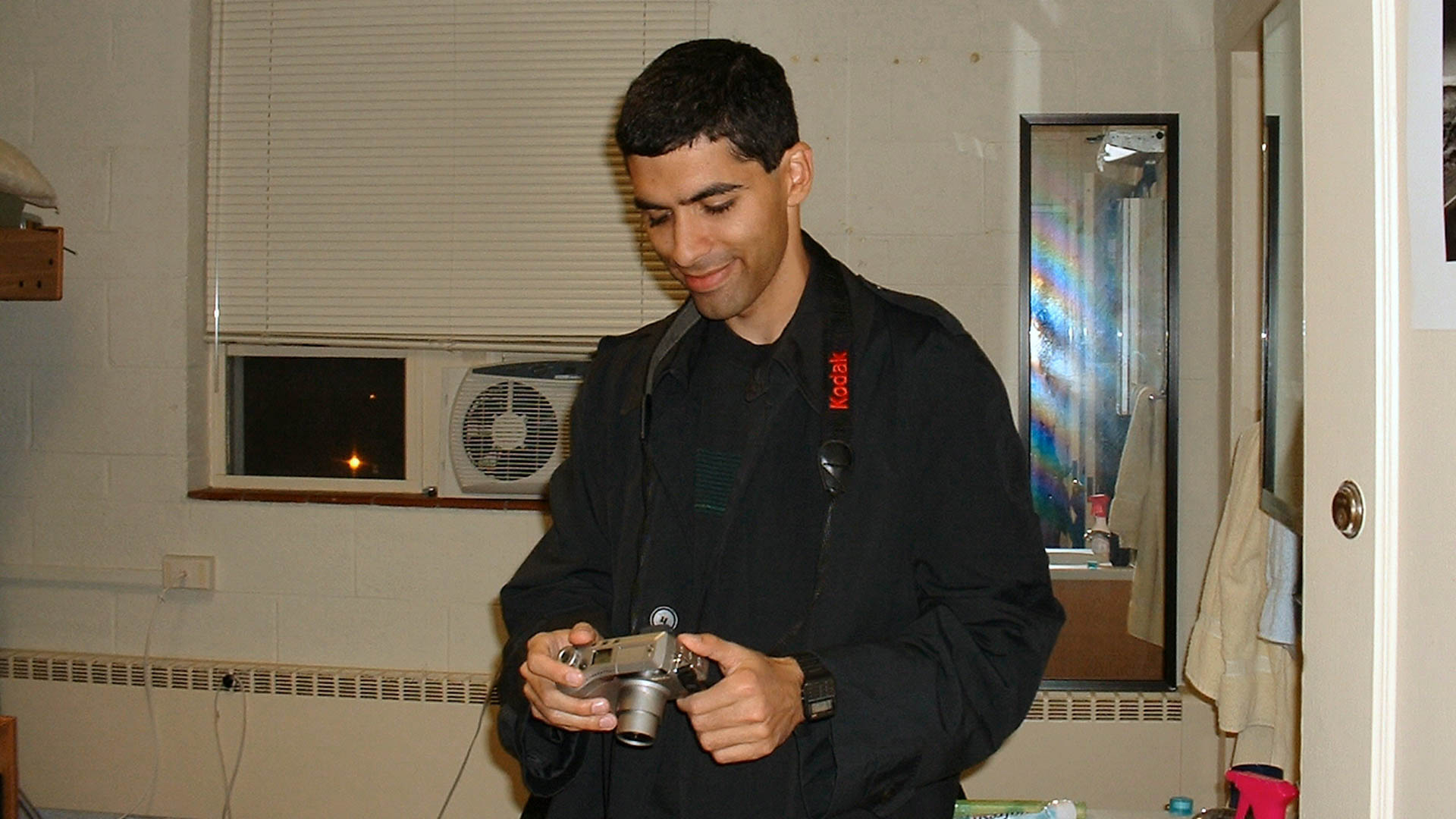

Work-life balance can be difficult to maintain, but rest is important. In my free time I take pictures, travel, go hiking, read fiction, and spend time with friends. Those activities encourage me to relax when work is difficult and to reflect on the bigger scope of my life.

2024 Update: Tenure

In 2024, Penn State granted me tenure and promotion to Associate Professor. This was the outcome of the standard "up or out" evaluation that either gives a professor considerable job security, which was the good news that I received, or ends their position. For the good news, I owe many thanks to my colleagues, collaborators, and advisees.

As mid-career faculty, I get to continue the idealism of a college student who decided more than 20 years ago to become a professor. The goals continue to inspire me. Create knowledge. Teach, mentor, and inspire. Compete for big things. Work at a cosmopolitan institution with engineers, scientists, doctors, law scholars, architects, philosophers, and artists as colleagues. Be an advocate for young people. Travel the world. All of that came to fruition, even if the details of the work sometimes aren't how I imagined them.

Professors do all those things, however, in a setting—higher education—known for its myriad obstacles. The public ones are daunting, and some of the hidden ones are monstrous. I sometimes tell my students that it can be overrated to know what you want to do for a living, because then you have to figure out how to do it, and that might not be easy. Luck plays a role, too, and one hopes to reminisce more than ruminate.

One of the rewards of being mid-career in academia is witnessing the story arcs of other people in my professional community: their triumphs, obstacles, uncertainties, and second acts. They play out slowly, and they build up over time. I have college friends who got into tenure-track positions sooner than I did, and some who are still trying. Many faculty have shared their stories with me, some after reading this article, and I hear a wider range of academic career-seeking experiences than I had imagined. I took longer than most, but with the perspective I have now, it's apparent I wasn't as alone as I had thought.

It's a troublesome road. I still can't imagine doing anything else, and often I get what I want, even if it takes a long time.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to friends and colleagues who provided feedback on drafts of this page. Thanks also to several of my research advisees and other students whose questions about my past convinced me to write this narrative.

This page was inspired in part by the "Advisor Biography" assignment that Penn State IST's PhD students must complete as part of their coursework.