Inglorious Proposals

Rejections and approvals in the search for research funding.

This page is part of my advice pages.

Read This First

I wrote this page to share timelines and observations from my proposals for research funding. I provide an overview of all the proposals I submitted during my first five years as tenure-stream faculty at Penn State, then provide three case studies of seeking funding from the US National Science Foundation (NSF). One produced funding on the second proposal (i.e., after a resubmission), one never produced funding after a series of seven proposals, and one produced funding on the first proposal. My roles in the proposals included being a PI ("principal investigator", the person who NSF recognizes as leading a proposal), being a co-PI (someone who NSF recognizes having a secondary leadership role, like a co-pilot), and having no official role but being the intellectual lead. They represent a subset of the much larger set of proposals I've participated in as faculty.

This page may be useful for faculty who are just getting started with submitting NSF proposals, or other people who are curious about them. The process of applying for funding is often hidden from students and the public, and its status among research activities is often questioned—hence inglorious in the title. However, this page is not a guide to writing proposals: instead I provide chronology case studies for three of the proposals I've worked on, to illustrate some possible paths and outcomes. Much advice exists on how to write good proposals, but relatively few resources describe the genesis of the ideas behind them or the lead-up prior to writing them. My hope is that examples like mine can illustrate what's normal for timing, preliminary work, and similar parameters.

I submitted all the proposals I describe on this page from academic units with strong research missions at R1 universities, and the external proposals in the case studies are all to CISE, NSF's directorate for computing and information science. Note that norms and procedures may vary by discipline, funding source (e.g., NSF, DARPA, NIH, etc.), funding goal (research, education, infrastructure, etc.), and other factors.

Several links on this page go to my Guide to Professorspeak. Tenure Worth Wanting also contains advice for pretenure faculty. Aspiring faculty also may wish to read my guide to the tenure-track job market.

This page contains unofficial information, and any errors are mine.

Contents

The Big Picture

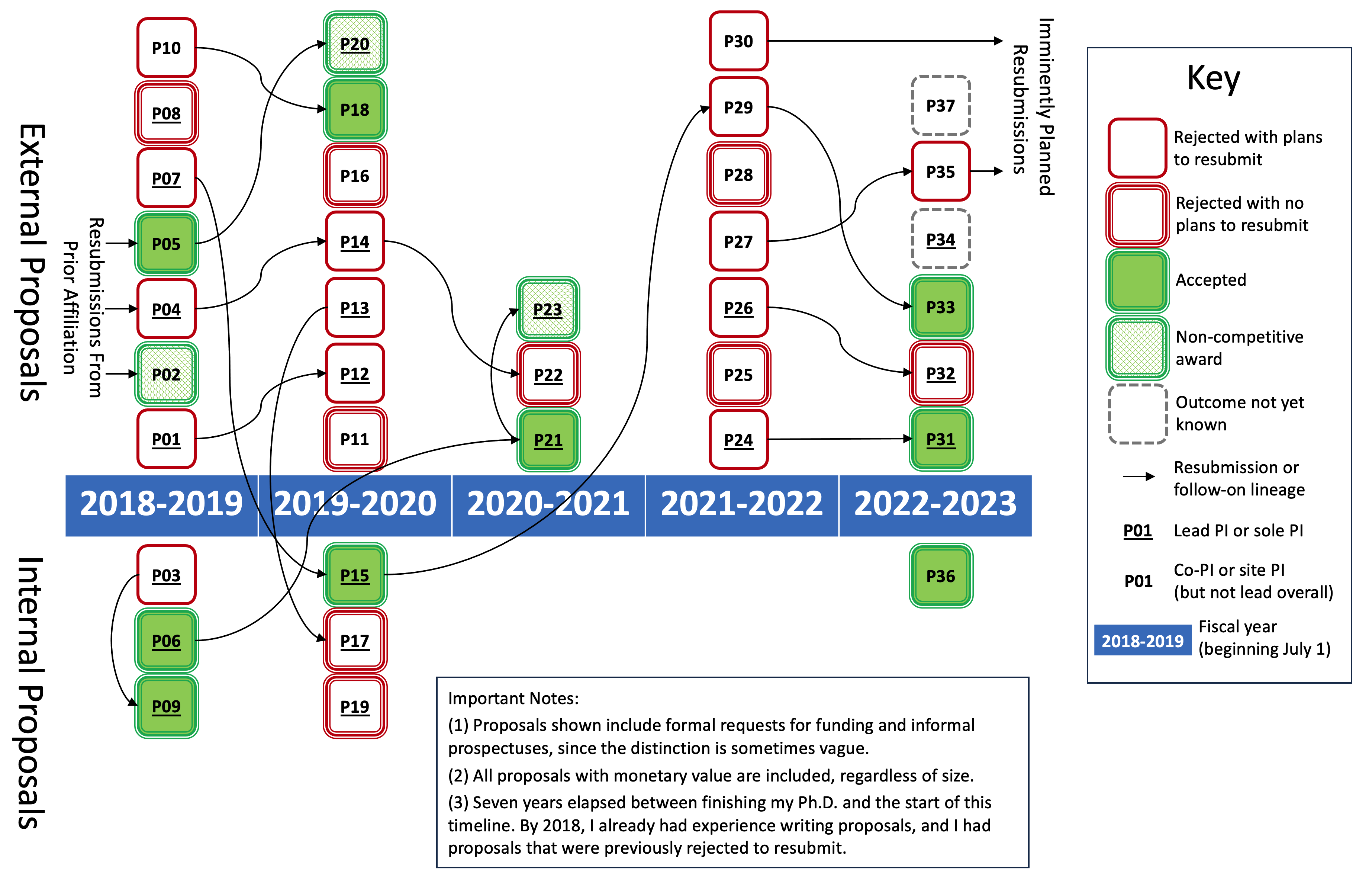

The below diagram shows all the funding proposals I submitted during my first five fiscal years at Penn State. It includes proposals of all sizes and degrees of formality, as long as they had monetary value. Note that I had significant prior experience working on funding proposals prior to arriving at Penn State, perhaps more than a typical starting faculty member. I arrived with skills that other faculty may have needed time to accumulate, and I had proposals ready to be revised and resubmitted.

This diagram should not be taken as an example of typical grant-writing activity for a pre-tenure professor, chiefly because there's not enough public information to establish what is typical. Variations in prior experience, research field, acceptance rate, career goals, and the culture of one's academic unit also make generalizations difficult.

However, the diagram illustrates the space for variation in persistence and outcomes. Some accepted external proposals followed seed-funded proposals, and some began outright as external proposals. Some proposals were rejected and we (or I) did not resubmit them; that might have been because they were for a one-time opportunity, the PI team was no longer able to work together, or the idea appeared to be infeasible. Some were rejected even after several tries.

Some observations:

- Internal grants were helpful for getting projects started. P06 and P15 led to NSF funding. P09 and P36 may yet in the future.

- 2020-2021 was a relative lull, because of the pandemic. I was in a privileged position for many reasons, but there was still an impact on nearly every aspect of my work.

- 2021-2022 looks like a terrible year, but note the successes prior to it. A year of all-rejections had less of an impact when I already had ongoing multi-year projects. Also, subsequently revising and resubmitting these proposals was less work than writing them from scratch. Two NSF proposals I submitted that year led to successful submissions the following year.

The three case studies below appear in this diagram. P07-P15-P29-P33 is Steady Pace, P04-P14-P22 is Seven Tries, and P06-P21 is Team Effort.

Case Studies

I use the academic calendar to divide up calendar years in the timelines below. Roughly speaking, Spring is January through early May, Summer is mid-May through early August, and Fall is mid-August through December.

Steady Pace

Briefly: Five and a half years elapsed between the genesis of the idea for the proposal and receiving funding. The proposal was funded on the second try.

Fall 2017: I read a report from a think tank that gave me an idea for a research direction. I didn't have the time or resources to pursue it, so I wrote it down in a list of research ideas I keep for future use.

Fall 2018: After moving to PSU, I revisited the idea and started talking with a colleague about it. She was interested too and had some thoughts about it, and soon the idea evolved to become jointly ours. We began looking for a graduate student to work on a small preliminary version of the idea ("mini-idea" below) and some seed funding to support the student.

Spring 2019: We submitted a "pre-proposal prospectus" to a special limited-time NSF funding opportunity. NSF rejected it.

Fall 2019: We recruited an MS student to work on the mini-idea with us and we applied for a seed grant from the university ($25K from PSU's Center for Social Data Analytics), which we received.

Spring 2020: The MS student told us she was enjoying research so much that she planned to switch to the PhD program. This wasn't directly related to getting the grant, but it was nice.

Fall 2020: We submitted a paper to a conference with the results of the mini-idea. (Researchers in many fields focus their publishing in journals, but in computing we tend to focus on publishing in conferences instead.)

Spring 2021: The conference accepted the paper for publication. This gave us an important supporting piece for a grant proposal, by demonstrating the merit of the full-sized idea.

Fall 2021: We decided we had enough material to write a full proposal to NSF. It would be for $500K, more money than our prior NSF attempt and much more than the seed grant from the university. We decided to switch roles for this proposal: my colleague would lead by being the PI ("principal investigator") and I would be a co-PI. Also, we brought onboard a second co-PI who had relevant knowledge.

Spring 2022: We submitted the proposal.

Summer 2022: NSF rejected the proposal, but the reviews were generally supportive. We decided to try again. For unrelated reasons, the second co-PI had to drop out of the proposal. A new solicitation let us increase our budget to $600K.

Fall 2022: We made changes to the proposal and submitted it a second time.

Spring 2023: NSF gave us the grant.

Seven Tries

Briefly: I led seven submissions of a grant proposal: two as a postdoc, two in my first faculty position, and three in my second faculty position. The proposal never received funding.

Fall 2014: As a postdoc at CMU, I told my supervisor that I was interested in leading an NSF grant proposal, and I suggested an idea based upon my research over the past year. He suggested we apply for a "Small", with a budget of $500K. My supervisor would need to be the PI because I wasn't eligible, and I would ghost-write most of the proposal. We recruited a second faculty member to be a co-PI. She added some domain-specific applications to the project, which prior to her involvement had been fairly abstract.

Spring 2015: Early in the semester we submitted the proposal. We had gone from a basic idea to a submission in under two months, including Winter Break.

Summer 2015: NSF rejected our proposal. The scores were middling and the reviews showed some clear directions for improvement.

Fall 2015: We revised the proposal and submitted it a second time.

Spring 2016: NSF rejected our proposal a second time. The scores had improved slightly.

Fall 2016: I moved to UC to start as faculty. The two faculty members I had previously worked with on the proposal turned it over to me, and I continued working on it alone, removing the parts that they wrote and replacing them with my ideas. The former co-PI agreed to give input to the project if the proposal was accepted, and she provided a letter to formalize that in the proposal. I revised the proposal and submitted it a third time.

Spring 2017: NSF rejected the proposal. The reviewers' scores went down slightly.

Summer 2017: My college funded me on a trip to Washington, DC to meet with program officers at NSF and NIH. I talked with the program officer who had been receiving my proposal, and she provided some feedback.

Fall 2017: I revised the proposal, including changes to follow the program officer's advice. I submitted the proposal a fourth time.

Spring 2018: Early in the year, an NSF program officer contacted me about a pre-review problem in the proposal and recommended that I withdraw it, which I did. Separately, I recruited an MS student in his final year to work on a miniature proof-of-concept version of the idea in the proposal.

Summer 2018: The MS student graduated, having written his thesis on the proof-of-concept work. He also submitted a paper about it to a conference, and it was accepted for publication.

Fall 2018: I moved from UC to PSU. I submitted a miniature version of the proposal to a private funding call, and it was rejected. Later in the semester, I found another faculty member whose interests aligned with the proposal ideas, and I asked him to join as a co-PI. We revised the proposal, including the MS student's preliminary work, and submitted it a fifth time.

Spring 2019: NSF rejected the proposal. The scores were an improvement over the previous time.

Fall 2019: We recruited a PhD student for more proof-of-concept work. We made some modest changes to the proposal to adjust for reviewers' comments and submitted it a sixth time.

Spring 2020: NSF rejected the proposal. The scores were slightly lower than last time.

Fall 2020: We made the most substantial changes to the proposal since the initial draft. We needed to modernize it, as the research landscape around it had changed substantially. We submitted it a seventh time.

Spring 2021: NSF rejected the proposal. The reviewers' scores were again lower than last time, and some were confused by our modernization efforts. I had other ideas I wanted to spend more time on, and I was less enthusiastic about this one than I had been in the past. I decided to set it aside. The PhD student switched to a different project, though a year later we would publish his proof-of-concept work in a conference.

Team Effort

Briefly: I led a team of four PIs across three organizations to submit a $1.2M proposal, which we received on the first try. Three years elapsed before the first discussion of the proposal idea and receiving the funding.

Spring 2018: While interviewing for a faculty position at PSU, a faculty member had an idea for a project at the intersection between our research interests. Neither of us could make it happen alone. I wrote it down in my list of research ideas for future use.

Fall 2018: I moved to PSU and reconnected with the faculty member about the idea. We applied for a seed grant from our college to support a graduate student for a year to work on a small version of the project.

Spring 2019: We received the seed grant. We hired a student to start on the project in fall semester, when he would join the PhD program.

Fall 2019: The PhD student started working and soon had preliminary results, including a demo we could share with potential collaborators.

Spring 2020: We asked for a one-year renewal of the seed grant, and we received it.

We had a conversation with a potential collaborator who could bring in relevant expertise that neither of us had, but it didn't seem like a good fit.

We submitted our first paper about the project to a conference. (We would submit two others during the period covered by this timeline, eventually getting them published, but this was the first and the most central to the project. For clarity, I've omitted the others from the timeline below.)

Summer 2020: We began planning to submit an NSF grant proposal in the fall. Initially I leaned toward a "Small" (a grant for up to $500K), but after speaking with several faculty I decided on a "Medium" (up to $1.2M), which would enable us to recruit more collaborators and support more students. I had a conversation with another potential collaborator; we had been postdoc labmates at CMU and now worked as faculty at different universities. He was enthusiastic. We needed a fourth person to fit a key role (the same role I had been trying to fill in the spring), and he had a suggestion for a person at a nonprofit organization. We contacted her and she was willing to join. That completed our "PI team" of four: I was the lead PI, my collaborator at PSU was a co-PI, and the two additional people were PIs at their respective organizations.

Meanwhile an MS student joined the project, increasing our rate of progress.

The first paper submission was rejected, and we revised it and resubmitted it to a second conference.

Fall 2020: We wrote the proposal and submitted it. With four PIs spread across three sites, coordinating our work was a task itself. Staff at all the sites also coordinated to support us, and students contributed edits and a small amount of text.

The second paper submission was rejected. We revised it and resubmitted it to a third conference.

Spring 2021: A program officer at NSF asked us to respond to a potential criticism of the project. We drafted a response and sent it to her. She then told us that she would recommend the proposal for funding, and in a few weeks NSF gave us the grant.

The MS student graduated, having written her thesis on her work with our project.

The third paper submission was rejected. We revised it and submitted it to a fourth conference, which would finally accept it in Summer 2021.

Reflections

Ideas

Activities prior to getting funding include generating proof-of-concept results, finding collaborators, writing the proposal, waiting for a result, and (potentially) revising and resubmitting the proposal. Intuitively, the further a proposal idea is from a PI's prior work, the more time they are likely to need to prepare it.

Sometimes the lead-up to a proposal is the result of a prior project, which can save time. That was the case for Team Effort and Seven Tries. In contrast, Steady Pace was a relatively new idea for my research portfolio.

My proposals to date have been an assortment of those that followed from my prior work (sometimes tracing back to my postdoc and PhD positions), those on adjacent but new-to-me topics, and those further away from my prior work that someone asked me to join. I think of this assortment as a "breadth and depth" strategy that supports both professional development and research impact.

Collaborators

One of the PIs on Team Effort was a former labmate from one of my postdoc positions. My co-PIs on Team Effort and Seven Tries and the PI on Steady Pace were both colleagues whom I had initially spoken with about topics other than grant proposals. Personal connections are sometimes involved: I've also submitted proposals with a labmate from graduate school and a friend from college who also ended up in academia. In those cases it was helpful for us to remember each other and to know something about our respective interests.

Networking sometimes has cynical, fatigue-inducing connotations. When I got to know the collaborators for these proposals, I didn't think of the interaction as explicit networking so much as getting to know people and being curious about their interests and ideas. Acute attention on finding collaborators creates an illusion of pervasive intentionality. There are many, many other researchers whom I've gotten to know the same way and haven't submitted grant proposals with, and possibly never will.

I once arranged a meeting with a colleague with the explicit goal of generating an idea for a proposal we could submit together. We were unnaturally trying to force the process to start, and we were unsuccessful.

Teamwork

Staff, and sometimes students, are heroes in the process. Many different documents go into an NSF proposal, and the staff usher all of them into place. They also help with budgeting and perform compliance checking. They're patient when I need help understanding how procedures work and when I need several revisions to a budget. Students' research activities provide background material for proposals and support writing them confidently. I've occasionally asked students to write small amounts of proposal text, to help organize references, or to copyedit. Thinking of staff and students as team members supports everyone's morale, including mine (i.e., none of us are working alone).

When we submitted Team Effort, I sent an email thanking everyone involved whom I had direct contact with. This was eight people: my co-PI at PSU, the two PIs at other institutions, two staff at PSU, one staff member at another institution, a student who wrote a couple paragraphs for the project description, and a student who copyedited our work.

Career Context

Seven Tries was never funded. Its core ideas remained the same while research trends had changed. My research profile had changed too: I had other projects going on, and those were attracting greater attention and resources. At the time of the first submission, I was a postdoc focusing intensely on a few projects; in contrast, by the seventh submission, I had been faculty for several years and I worked on many projects in parallel. That redundancy gave me enough options for productivity that I could stop working on a proposal that perpetually struggled.

Three years after the final rejection of Seven Tries, a friend at a different university received an NSF grant to study a very similar problem. I was surprised, but not disappointed. Instead, I was glad (relieved, even) that someone would continue research on a topic that I cared about but couldn't get funded.

Luck

Preliminary work for Seven Tries led to two publications, but NSF never funded it. Meanwhile, Team Effort was funded on the first try, but the nucleus of our preliminary work required four attempts to publish. Ironically, sometimes publishable ideas are difficult to get funding for, and occasionally it's easier to get funding for an idea than it is to publish about it.

There is an abundance of advice (and even folklore) about how to get a grant proposal accepted, but skill and hard work remain chiefly a baseline. Some luck is always required. I chose to write about three proposals because they illustrated specific things, and they're only a small subset of the proposals I've worked on. Creating many opportunities for luck, while still valuing quality over quantity, increases the chances of some success.

About the Pictures

I added them to break up the text; all of them are mine. I am a photographer in my spare time.