Guide for Research Conferences

This guide is part of my advice pages.

Read This First

I created this guide to help people understand how to publish their research in computer science and information science ("CS/IS") conferences. Toward the end of the guide, I include some information on how CS/IS journals and workshops differ from conferences.

Important preliminary notes:

- My Guide for Scholarly Writing and Guide for Citations and References are important companions to this guide. You should read them too.

- Typically, the first time you're a lead author on a submission will be the hardest. The upside is that most of the knowledge you gain is transferable to other venues and papers, so that future submissions will be easier.

- I've organized this guide into steps for the publication process. I recommend reading the complete guide once and then later checking in with it at the beginning of each stage.

- Publishing expectations can vary radically by discipline, and sometimes by research community. For example, in CS/IS conferences are typically the premier publication venues, but in many other disciplines journals are more important. This guide contains norms that my advisees should become familiar with, and they're fairly common across CS/IS, but your mileage may vary.

Finally, if you're not a member of my lab and you find this guide useful then please email me (see "Contacting Me" instructions) or let me know on Bluesky.

The Guide

- The Professor's View

- Before You Write

- Finding the Right Conference

- Do You Have Enough Material for a Paper?

- Reading the Call for Papers

- Assembling the Submission

- Preparation

- Naming the Manuscript's Project or File

- Writing Well and Avoiding Plagiarism

- How to Organize the Paper

- Preparing Supplementary Materials

- Determining Authorship and Author Order

- Anonymity for Peer Review

- Tell Your Co-Authors When You've Completed the Submission

- After Submission

- Keep All Your Co-Authors Informed About Publication Progress

- Participating in an Author Response Period

- If the Submission is Accepted

- If the Submission is Rejected

- Attending a Conference

- What Happens at a Conference?

- What Should I Do at a Conference?

- I Feel Awkward About Starting Conversations at a Conference. What Can I Do?

- Which is Better, an Oral Presentation or a Poster Presentation?

- What's it Like to Present a Poster at a Poster Session?

- Can I Tell a Presenter a Comment (Rather Than a Question) During Post-Talk Q&A?

- How Do Attendees Pay For Conference Registration and Travel?

- What Should I Wear?

- Miscellany

- How Are Journals Different From Conferences?

- How Are Workshops Different From Conferences?

- About the Pictures

The Professor's View

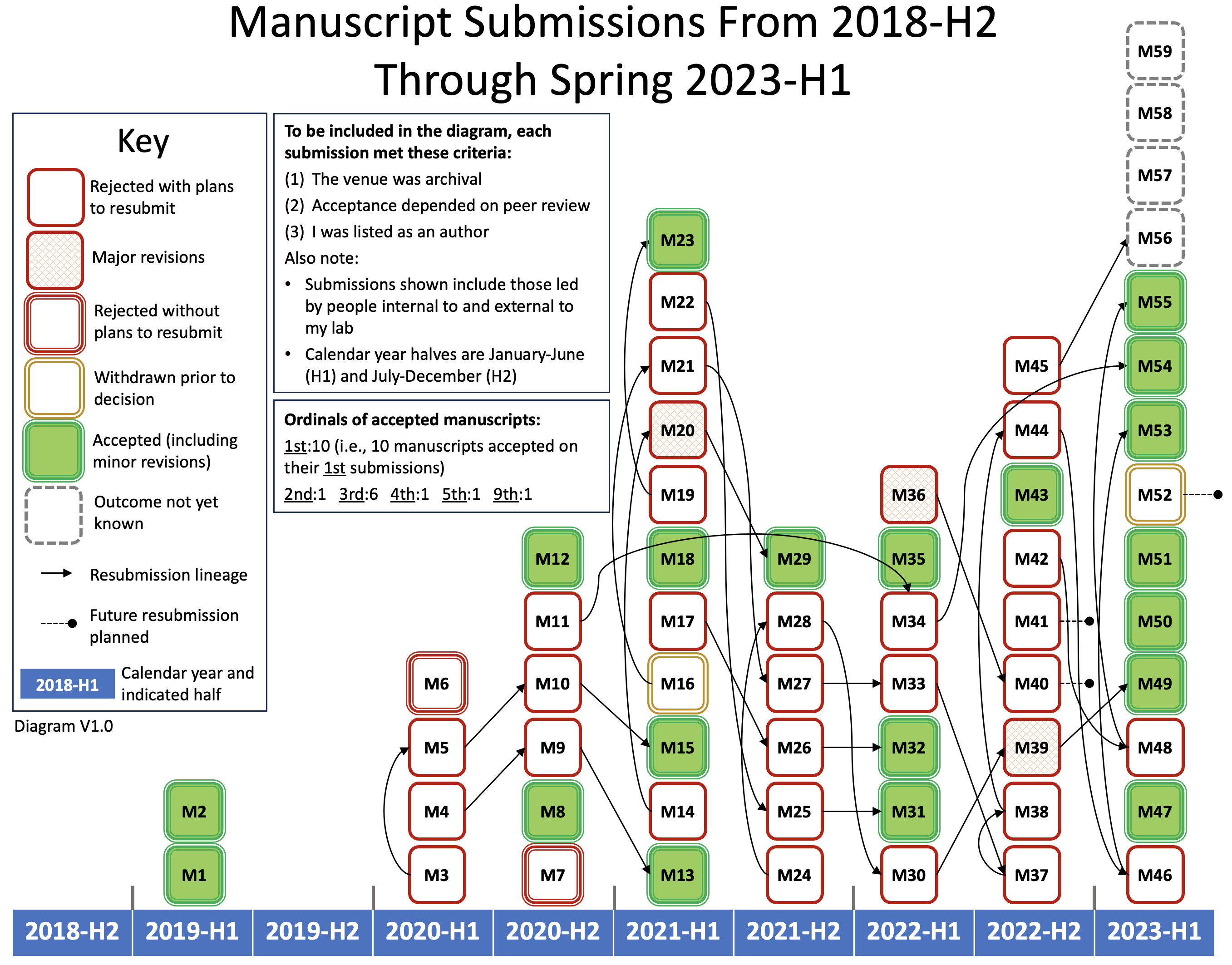

This diagram shows manuscript submissions from my lab during my first five years at Penn State. Note that it shouldn't be taken as an example of a typical professor's work, because typical is poorly defined among faculty. Variations exist in career seniority, professional goals, funding, institutional culture, and luck.

This aggregate view provides insights that might otherwise be hidden from student researchers. Importantly, nearly all manuscripts that we submitted got published, though some needed several revisions and resubmissions. The number of resubmissions that manuscripts needed varied widely. Also, although diagramming might suggest that manuscripts are fungible, each one has a unique story. Among them are a manuscript that took nine tries to get accepted and then won a best paper award; the manuscript that took four tries while the grant proposal it seeded was awarded on the first try; and more than once when undergraduates first-authoring for the first time got manuscripts accepted on the first submission.

There is much more to research than publishing, but communicating your work in a manuscript is important for reflecting on the prior activities in the research process. Writing a manuscript often leads to new findings or takeaways that the researchers previously didn't realize. Published research findings are also foundational for the progress of a discipline, which moves forward only with contributions from many people.

Before You Write

Finding the Right Conference

You'll want to find a conference that's both the right fit for your work and has a submission deadline that is compatible with when your work will be ready. I recommend signing up for your research community's email lists long before you plan to submit a manuscript. This will help you to become aware of the conferences in your field and what time of the year their deadlines tend to be.

Many conferences are held on an annual basis, but some are held every other year or every few years. Looking at the proceedings from recent years is helpful to determine whether your research will fit in.

Talking with your advisor is also a helpful part of choosing right venue. They will know if a conference is reputable (i.e., it's a worthwhile place to publish) and if it has unwritten themes or quirks to be aware of. If your advisor haven't published in a particular conference before, they may be able to help you evaluate it by looking at the list of organizers or recent proceedings.

Do You Have Enough Material for a Paper?

There's no simple way to determine this, but you can ask yourself questions like:

- Does your work have results, and do you have interesting observations about the meaning of the results?

- Does your work represent new knowledge about something?

- Placed next to prior related work, does yours contrast with it in a novel way?

- Have you created a resource for the research community that you're ready to share?

Some "yes" answers to the above questions are a good sign, although they're neither necessary nor sufficient. Again, your advisor can help you decide.

Reading the Call for Papers

A call for papers (sometimes CFP) is an announcement issued by a conference with information on how to submit a paper. If you're planning to submit to a conference, you should keep its CFP bookmarked and check in on it often in case it changes. A CFP contains lots of useful information, including:

- Important dates, and in particular, when submissions are due

- A list of topics the conference focuses upon

- Your options for a submission type (e.g., short or long papers)

- Required templates for preparing your manuscript

- Requirements for anonymity in the manuscript

- Other rules you must follow for a successful submission

- A link to a page where you upload your submission

- Whether the conference is archival (i.e., whether the proceedings are formally published)

- Whom to contact if you have questions

Sometimes a conference issues an updated CFP (e.g., a "second call for papers") with new information such as deadline extensions.

You can find the CFP for a conference on the conference's website. Third-party CFP aggregators such as WikiCFP exist, but there is no guarantee that they are accurate or up-to-date. It's best to rely upon the conference's own website instead.

Assembling the Submission

Preparation

I ask my advisees to follow this procedure.

At least 21 days before the submission deadline, do the following:

- Download the template in the CFP and use it to create an empty document for your manuscript: This makes it as easy as possible for you to begin writing or to drop in figures when you are ready. Note that you may need to do this further in advance to have a full draft ready by two weeks out, which I ask for below.

- Register on the submission site: Getting this out of the way early saves you from technical problems later. Submission sites occasionally malfunction, especially close to deadlines for busy conferences.

At least 14 days before the submission deadline, do the following:

- Share a full draft of the manuscript with all co-authors: If you're using an online editor, send us a link and make sure we are able to edit the project. In the same email, include the submission deadline and a link to the CFP.

- Ask me for help choosing submission tracks and/or topics: Once you're logged into the submission site, you can see all the options for categorizing your submission. Note these options sometimes differ from options listed in the CFP, so choosing based upon the CFP is insufficient. My help is important, as I may know more than you do about what the options mean. Good selections guide your paper toward the reviewers that are most receptive to your work. Poor selections lead to unnecessary paper rejections.

- Have an authorship discussion with me: We should do this during a meeting. The discussion should be about who belongs in the author list and the author order.

When these two- or three-week periods include holidays or breaks, observing the deadlines further in advance is appropriate.

Within the three weeks before a submission deadline, expect the manuscript to be a prominent topic at meetings, and probably the first topic that we should discuss. Note that discussing research results is different from discussing the manuscript. Also be prepared for revisions in response to coauthors' comments to take significant time and effort.

Meeting these deadlines shows respect for coauthors and helps us find the time to provide effective feedback on the manuscript. If these tasks slip later, the likelihood increases that I will ask you to postpone the submission, either because coauthors (including me) won't have the time to properly review the manuscript or because it does not appear to be ready.

Naming the Manuscript's Project and/or File

Immediately after you create the manuscript from the template, rename the project (e.g., if using Overleaf) or the word processing file (e.g., if using Microsoft Word). I prefer that my advisees use the convention "[conference abbreviation] [year] - [first author's first name]". For example, a name like "EMNLP 2015 - Alan" helps me distinguish between my students' manuscripts. It will also help you stay organized if you are involved with more submissions in the future.

You should keep a copy of the original template around to refer to it, but you should also immediately customize (as above) the name for the typesetting file or word processing file that contains your work. This allows you to quickly distinguish between the template and your own work. Occasionally, confusing names lead to mistakes with disasterous results (i.e., deleted work).

Writing Well and Avoiding Plagiarism

If you didn't already, check out my guides about those topics.

If there's a question about style that you can't resolve, check the papers that received the best paper awards from prior years of the conference you've chosen.

How to Organize the Paper

The structure of your paper (e.g., what sections to include) will depend in part on the nature of your contribution. Are you showcasing results from a computational experiment? Are you sharing the outcome of a user study? Did you perform an exploratory analysis of a dataset that you're sharing with the research community? Are you writing a survey paper to provide an overview of research on a certain topic? Find papers in the conference you've chosen that make contributions of a similar nature to yours, and consider following their structure.

Preparing Supplementary Materials

A conference may ask that you submit supplementary materials, such as your dataset or source code, alongside a manuscript. You should plan on providing supplementary materials if at all possible, and you should also prepare documentation to accompany them. The documentation should explain what the materials are to an audience that has only skimmed your paper. It should be well-written, but the format typically can be as simple as a text file.

If the full dataset or source code is too large to upload, submit an illustrative subset of it instead and explain in the documentation.

Determining Authorship and Author Order

The author list should contain all people who made substantial intellecutal contributions, including research guidance, software development, examination of results, writing, obtaining funding, and other major activities. It's best when authorship is determined via consensus, but when there is disagreement, a senior author (such as the advisor of the lead student on the manuscript) should make the final decision. Sometimes people who make minor contributions, like providing useful feedback once in a conversation or an email, are listed in the acknowledgements instead.

CRediT (Contributor Roles Taxonomy) lists types of contributions that may merit authorship. Optionally, my advisees may choose to include CRediT statements in their publications.

A common CS/IS convention on author order is to list students first, in order by significance of contribution, and then to list faculty afterward. Typically the last author is the first student author's advisor or the leading faculty member for the overall project. There are exceptions to these rules, though; sometimes all faculty (or all authors) are listed in alphabetical order. Sometimes a faculty member comes first if they contributed more than the students.

Anonymity for Peer Review

Many conferences use peer review to select papers: this means that other researchers review your paper to determine whether it merits publication. To avoid personal biases or conflicts of interest, most conferences use double-blind review: the authors don't know the identities of the reviewers, and the reviewers don't know the identities of the authors. Occasionally a conference may use single-blind review: the authors don't know the identities of the reviewers, but the reviewers know the identities of the authors. The CFP will specify the review procedure and whether you need to anonymize your submission.

If anonymization is necessary, leave out the authors' names and any evidence of their affiliations in the manuscript. This includes URLs that would imply your affiliation; you can replace them with a placeholder like "[URL redacted for double blind review]". Also leave out the acknowledgements. You can add all of this information to the final version of the manuscript if it's accepted.

Citing your prior work in an anonymous manuscript is fine: simply refer to it in the third person.

Keep in mind that some venues reject manuscripts without review if they don't meet anonymization requirements.

Tell Your Co-Authors When You've Completed the Submission

Once you've submitted the manuscript, the submission site will send you a confirmation email. Forward the email to your co-authors immediately, and attach a copy of the manuscript to it. This serves as an important confirmation to your co-authors that you completed the process.

After Submission

Keep All Your Co-Authors Informed About Publication Progress

If you are the corresponding author for a submitted manuscript (i.e., the person who communicates with the publication venue), promptly forward to your co-authors copies of submission confirmations, peer reviews, submission outcomes, and other official emails. These notices will help your co-authors to understand what is happening to the manuscript and to plan for their obligations.

Participating in an Author Response Period

Some conferences allow authors of submissions to read and respond to the reviewers' comments prior to a final decision being made. Carefully follow the instructions from the conference for the author response period. Typically, you are called upon only to respond to reviewers' questions and to correct factual misunderstandings. You should not express disgareement with reviewers' opinions or debate with them. Such responses will not sway them, and you risk alienating other reviewers or the conference organizers. Counterintuitively, the author response period isn't an opportunity to vie for a better score; the goal is simply to help reveiwers with specific details your work that they found puzzling.

I created this template to help my research advisees understand how to structure an author response. The per-reviewer structure helps reviewers understand which parts of your response are respectively most relevant to them. You can adjust the first sentence and the last sentence to fit your personal style, or you can keep the wording I included.

I always recommend a "soft touch" for author responses: be helpful and cordial, but be brief. Typical reviewers for a conference must read author responses for several manuscripts. A short response maximizes the likelihood that your reviewers will read all of it. Long responses rarely sway reviewers, and they are not worth your investment of time and energy.

It's also customary to use the author response to thank reviewers for their feedback.

If the Submission is Accepted

Congratulations! Talk with your advisor about what changes to make prior to submitting the final version of the manuscript. The final version is sometimes called the "camera-ready" version for historical reasons. Typically you're not required to make any changes, but you should use the reviewers' feedback to improve the paper.

Sometimes venues accept manuscripts "with shepherding". This means that a manuscript is conditionally accepted, and it needs specific changes before it can be fully accepted. Someone working with the conference (a "shepherd") communicates with the authors and reads their manuscript revisions to ensure that the necessary changes are made.

Remember to de-anonymize the manuscript if necessary. Also, if your research was supported by a grant, the grant number and the funding agency should appear in the acknowledgements. Your advisor can provide the appropriate information.

If you're a member of my lab and you need to make a slide deck or a poster for a conference, read the section on lab branding in the Guide for Lab Resources.

If the Submission is Rejected

Don't take it personally. Rejection is the most common outcome for submissions to competitive conferences, sometimes by a factor of four or more. Good papers are sometimes rejected simply because a conference doesn't have room to accommodate them. If you're feeling acutely discouraged, read my Thoughts on Failure for some perspective.

When revising a rejected paper for submission elsewhere, it's helpful to make a spreadsheet listing reviewers' criticisms and changes you will make to improve the paper. Here is an example revisions spreadsheet, and here is a blank template. If you share the spreadsheet you create with your co-authors, they can provide feedback on the changes you propose. A spreadsheet like this also helps co-authors divide up the work.

As a graduate student, my first three first-author submissions were all rejected. As a postdoc, one of my publications was rejected twice before it was both (1) accepted by the first conference that had rejected it and (2) a finalist for the conference's best paper award.

Attending a Conference

I've written this section primarily for in-person conferences, but most of it applies to virtual conferences too.

What Happens at a Conference?

Attendees go to conference events, and they talk with each other. A typical conference's "main program" lasts one to three days, perhaps with a few more days before or after for workshops and tutorials.

Below are some typical events in a conference program, although a conference may not include all of them. Smaller conferences schedule one event at a time, while larger conferences have multiple events running in parallel.

- An opening session: The organizers briefly talk about the conference program, submission statistics (e.g., the number of submissions and the acceptance rate), and the work that went into organizing the conference.

- Oral presentation sessions: Each paper that the conference accepted for oral presentation receives a time slot in the schedule. An author presents the paper using slides, and afterward they take questions from the audience. To save time, related papers are bundled together into sessions, so that the transition between presentations is brief.

- Poster presentation sessions: Each paper accepted for poster presentation is assigned a place to display a poster, often in a large room with many other posters at once. One or more authors stand by their poster and take questions from attendees who visit it.

- Demo sessions: These are similar to poster sessions, and the two are sometimes combined. Each accepted demo submission is assigned a place to set up a demonstration of the relevant software or hardware.

- Lightning talks (sometimes "flash talks", etc.): Papers accepted for poster presentations or demos are sometimes allocated very short (e.g., one-minute) talks. They are rigidly timed, often with a line of presenters ready to take the stage. Instead of describing one's work in detail, the goal of a lightning talk is chiefly to entice attendees to visit the poster.

- Coffee breaks: These happen between events. Beverages and light snacks are served. These are one of several different opportunities to talk with other conference attendees.

- Lunch breaks: Sometimes you have to find your own lunch from nearby options, and sometimes the conference provides the meal. It's appropriate to try to go to lunch with other attendees, but try not to feel bad about going alone. I sometimes go to lunch by myself because I can't find other attendees who are available to come with me, or because I have a specific lunch destination in mind and I can't find anyone else who wants to go there.

- Social events: Conferences often have an evening reception or banquet. There may be entertainment, such as live music or a DJ. Some conferences also have organized outings to museums or sites of cultural interest.

- Plenary talks: These are the sessions that the organizers expect everyone will want to attend, with few or no other sessions happening in parallel with them. They may include talks for award-winning papers or special invited speakers.

- Workshops: These resemble mini-conferences for works in progress, clustered around specific topics. I describe them in more detail elsewhere in this guide.

- Tutorials: These are educational events themed around specific topics.

- A business meeting: The conference organizers discuss the conference's (or the sponsoring organization's) finances and governance.

- A closing session: The conference organizers thank everyone who helped run the event. Upcoming conferences may be announced or promoted.

What Should I Do at a Conference?

Do the following:

- Present your work: If you're scheduled to present, it's your top priority.

- Discuss research: Have conversations with a variety of other attendees about their work, your work, and the state of the research community. Plenary talks and presentations that just ended are good conversation starters.

- Find career opportunities: A conference is a networking opportunity, whether your next step is graduate school, a position in industry, a postdoc position, or a faculty position. Some conferences have exhibitor areas for sponsors from industry, and many of them are looking for interns or permanent hires.

- Learn about research: Attend as many presentations as you can, but don't feel guilty about missing a few of them if you're engaged in productive conversations about research or your career. Those kinds of interactions will benefit you more in the long run.

- Make friends: Not every conversation has to advance your research or your career, and professional pressures should not obscure your well-being. Talk with your peers, and find your people. If you stay in the field, you might see them again periodically at conferences for years to come.

Professional conduct is appropriate in all conference activities, including informal ones (e.g., going out for drinks). Sexism and racism persist in academia, and instances of them cause conference attendees to feel uncomfortable or marginalized. A good conference experience includes opportunities to relax and have fun, but you must always treat other attendees with respect.

I Feel Awkward About Starting Conversations at a Conference. What Can I Do?

Here are some thoughts:

- Some of the best conversation starters aren't research-related(!). The venue, the refreshments at the breaks, or the host city are easy ways to start a conversation. Say something positive about one of them and see where it goes. If you want to discuss research, you can do that next.

- "I enjoyed your talk" works surprisingly well as a conversation starter. People who have just given talks tend to be insecure about them. Your compliment can start a discussion, assuming you actually did enjoy the talk.

- People standing around looking bored or awkward during coffee breaks often will be happy to talk with you. They know they're supposed to be networking, and you're relieving them of the pressure. Sometimes they'll visibly relax when you start talking with them.

- You can talk with any attendee. As a graduate student I unknowingly began conversations with academic celebrities, and the distribution of their reactions resembled everyone else's: sometimes they were interested in talking, and sometimes they weren't. If you've got a meaningful topic to discuss, try it.

- It's OK if you don't know yet what your research is about. Don't feel obligated to spontaneously make up something. It's fine to say that you're figuring out what you want to do. Mention which sessions you've been to and which topics interest you the most.

Finally, if you have a productive conversation with an attendee and you're concerned about forgetting their name, you can ask them if you can use your phone to take a picture of their conference name tag. Exchanging business cards is also an option, though not everyone has their own.

Which is Better, an Oral Presentation or a Poster Presentation?

Neither is fundamentally better. An oral presentation gives the presenter several minutes to tell the audience the story of their work, but poster presentations allow the presenter to have discussions with other attendees about the work. Some people like oral presentations for their formality and decorum, and some people like poster presentations for the interactivity.

Conferences occasionally allow presenters to have both an oral presentation and a poster presentation. This is an excellent opportunity to get the advantages of both modes.

What's it Like to Present a Poster at a Poster Session?

Poster presentations are very different from oral presentations, which students typically have done in their classes. The conference will ask you to set up your poster in a room with several other posters, and you'll stand next to yours while conference attendees wander through the room. They will visit posters that interest them and talk with the presenters. Some conferences provide light refreshments during poster sessions. A lively poster session has the atmosphere of a professional networking event rather than a hushed lecture hall.

Attendees visiting your poster will sometimes ask you to tell them an overview of the work you're presenting. You should be prepared to answer this question with a brief summary, but it should be informal rather than carefully rehearsed.

During a conversation with someone who is interested in your poster, avoid monologues: never talk for more than a minute without letting the other person speak. Poster presenters who give monologues prevent attendees from asking questions, causing them to lose interest. They also prevent attendees from moving on when they want to visit other posters.

Can I Tell a Presenter a Comment (Rather Than a Question) During Post-Talk Q&A?

It's best to only ask questions during talk Q&A. If you have a comment rather than a question, talk with the presenter after the session ends.

How Do Attendees Pay For Conference Registration and Travel?

Students in CS/IS who have submissions accepted by a conference typically receive reimbursement from their advisor's lab or from their academic unit, although when multiple students share authorship it may be practical to send just one. Some conferences offer travel grants for students or volunteering opportunities in exchange for free registration. (These volunteering opportunities are a good way to meet other attendees, and I recommend applying for them.)

Professionals working in industry or government are typically reimbursed by their employers. Faculty receive reimbursement from their research funds or professional development funds.

Always confirm that you'll receive reimbursement for attending a conference rather than assuming.

What Should I Wear?

Business casual is appropriate for CS/IS conferences. I recommend choosing what's best for you from these pieces:

- A dressy collared shirt or a blouse

- Dressy slacks

- Business-y shoes that are comfortable to walk in

- A business-y dress or skirt

- A sport coat, nice sweater, or a dressy cardigan (though feel free to skip it if it's too warm)

However, opinions vary on conference attire. For reference, I identify as male and I would feel overdressed wearing a tie and/or suit; I rarely see attendees wearing those items. I would feel underdressed wearing a t-shirt, jeans, or shorts, although I often see a subset of attendees wearing those items. My typical conference outfit is a dressy shirt, khakis, a black belt, and black dress shoes.

Attire in a similar category of dressiness from non-Western cultures is also acceptable.

Miscellany

How Are Journals Different From Conferences?

In CS/IS, conference papers are often seen as more important than journal papers. (That's unusual: in many disciplines, journal papers are more important than conference papers.) Still, journal papers play an important role. They accept longer papers than conferences, permitting authors to document longer trajectories of work. One approach to a writing journal article is to integrate results from a conference paper (or multiple conference papers) with additional, unpublished results.

Journals are more likely to be single-blind than conferences, which tend to be double-blind.

Journal articles tend to take longer to publish. More than a year (or two) may pass between submission and publication. Submissions will sometimes go through multiple rounds of peer reviews and author revisions before the journal decides the manuscript is acceptable.

PhD students should aim to submit one or two journal papers before graduating.

How Are Workshops Different From Conferences?

Compared to conferences, workshops are more receptive to manuscripts that describe work in progress or preliminary results. They tend to be smaller events than conferences, with a greater emphasis on providing feedback to presenters and discussion amongst attendees.

Major conferences sometimes have workshops attached to them, i.e., the workshops use the same registration process, location, and other infrastructure as the main conference. Alternatively, sometimes workshops are independent events.

If you have a paper accepted to a conference that has workshops, you should browse the workshop list for opportunities to submit more of your work. Often the workshop submission deadlines are after the main conference's acceptance notification date.

Workshops are less likely to be archival than conferences or journals. When one isn't archival, you can use the opportunity to gather feedback on the ideas in a manuscript prior to submitting it to a conference. If the archival status is unclear, ask the organizers.

About the Pictures

I added them to break up the text; all of them are mine. I am a photographer in my spare time.